There’s no easy way to sum up the impact COVID-19 had on Central Florida’s real estate industry. When Orange County Mayor Jerry Demings issued the county’s first mandatory stay-at-home order a year ago on March 24, the reverberations could be felt immediately throughout every sector of the industry as much of the economy shut down.

The next 12 months would reveal the pandemic’s winners and losers, as the recovery and reopening were anything but even. Office workers set up shop at home, forcing a monumental shift in demand for permanent office space. The fast-changing migration patterns and market demands led to record sales in some sectors. While residential and industrial development thrived, traditional retail and hospitality-dependent business found themselves in a year-long funk.

With the vaccine rollout promising a return to normalcy, we take a look back at the roller coaster year in Orlando real estate.

Developers pause commercial construction

All of Orlando’s major theme parks shut down in mid-March, even before Demings’ official order. In April, Universal announced an indefinite pause on construction at the new Epic Universe theme park, by far the largest project in the entire region. So it was welcome news this month when parent company Comcast announced it was resuming work on the multibillion-dollar development. The projected opening date was pushed back from 2023 to 2025.

In August, Demings and the Board of County Commissioners bowed to public pressure and halted work on the more than $600 million expansion of the Orange County Convention Center.

Orlando’s Central Business District suffered, too. According to JLL’s year-end report, the pandemic caused a glut of office space in the downtown core as demand dropped by roughly 26% year-over-year. Class-A was hit the hardest, contributing 71% of the total change in vacancy during 2020.

Downtown Development Board Executive Director Thomas Chatmon said the pandemic created unprecedented uncertainties in the real estate market. “There have been some delays, slowing of the momentum of projects moving forward,” he said. “We don’t seem to have had many casualties, so far as development projects.”

In Creative Village, construction commenced on the EA Sports $62 million headquarters building and on the Mill Creek Residential’s 292-unit Modera apartment building. The Orlando Magic also broke ground on their new $70 million training facility, which also features a sports medicine clinic by AdventHealth.

Some of downtown’s highest-profile projects appear to have been put on a shelf.

The Magic’s $500 million Sports + Entertainment District was projected to start construction last year but is now delayed indefinitely. The master plan was redesigned in late 2019 to more than double the amount of office space from 200,000 square feet to 420,000 square feet, and to add more hotel rooms and retail space. Those changes made sense at the time, given the high occupancy rates in the downtown market and demand for modern, Class-A offices.

Lincoln Property Company delivered its SunTrust Plaza at Church Street Station, fully leased in 2020. It was the first new office tower built downtown in over a decade. But plans to break ground last spring on a second mixed-use tower, with a hotel and another 210,500 square feet of office space are on hiatus. Chatmon said he believes the second tower is still viable and moving forward, and two residential mixed-use towers that don’t have large office components are “moving forward in very definitive ways through the system.”

Franklin Street’s Yvonne Baker told GrowthSpotter large corporate users throughout the Orlando market canceled leases or gave back hundreds of thousands of square feet. “When you have huge pockets like that, you can’t justify building a new building,” she said. As demand and financing for new office space disappeared, other developers redesigned their projects in response to the new market.

Property Markets Group abruptly canceled the planned groundbreaking ceremony last March for its Society Orlando mixed-use tower at 434 N. Orange Ave. and halted work on the project. It was approved for a mix of retail, office and co-working space, and over 900 residential units across three towers– making it the largest multifamily project ever approved for downtown Orlando.

Over the next six months, PMG scaled everything back by about 40 percent. It eliminated one of the three residential towers and scrapped all of the office space.

Rick Colon, director of capital markets for Cushman & Wakefield, has suggested that office fundamentals for the Orlando market will recover, but perhaps not to pre-pandemic levels.

“You know, so to me, this was always going to be a trend that was going to take a little bit of time for us to fully understand,” he said during a recent panel discussion. “Early on in the pandemic, working from home really appeared to be working well for most people. But the trend has really reversed itself, and most folks I talked to were just very eager to get back into the office. So, investors are really put a heavy focus on the specific risks of each office deal. But I think the general consensus really from institutions is that the physical office is going to continue to play a very vital role in the lives of employees going forward.”

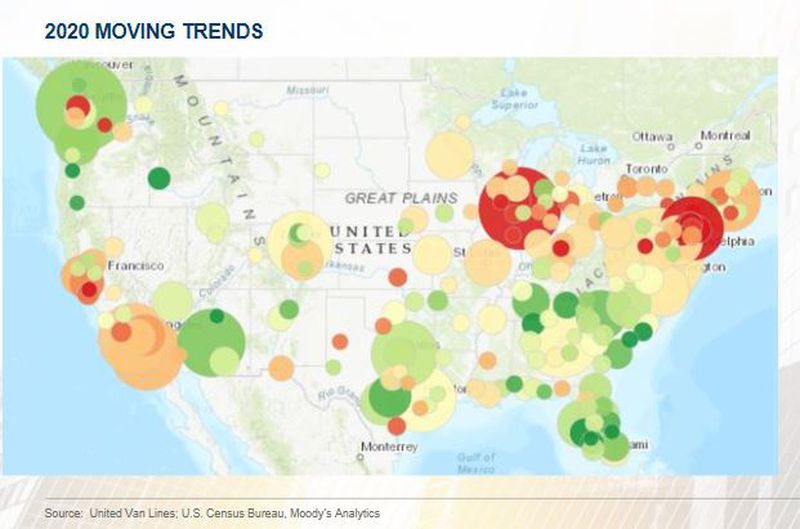

Metro Orlando among top MSAs in net migration

The pandemic and its financial repercussions both tested and accelerated some underlying trends in migration seen over the last five years.

Metros in Florida, specifically Tampa and Orlando, saw more people move in last year than other regions throughout the nation, while bigger cities in the southeast and west coast experienced more exits.

According to a February report by Redfin, Orlando gained 60,977 people, landing it as the third U.S. metro to add the most new residents in 2020 behind Phoenix with 82,000 and Dallas with 76,000.

At a “State of the Market” panel hosted by Cushman & Wakefield earlier this month, David Smith, Cushman & Wakefield’s global head of Occupier Research, said Orlando welcomed about 1,150 new residents per week last year.

He said on a macro level, the data shows an uptick of residents leaving the Northeast and Pacific Northwest and relocating to the warm suburban and urban climes found in the Sunbelt.

“That trend was happening pre-pandemic, that trend got accelerated by the pandemic, that trend will continue moving forward,” he said at the webinar. He estimates Orlando’s 380,000 new residents surveyed over the last 10 years will grow to 430,000 over the next 10 years.

Real estate investors and developers went to great lengths to keep a pulse on migration patterns to see any shifts brought on by the pandemic that may directly affect their investments and the markets they’re active in.

FCP, which redeveloped the AECOM building in downtown Orlando and has a growing multifamily portfolio in the area, went as far as using data that tracked cellphone locations of 3.8 million anonymous users to follow the latest shifts in relocation activity.

Data from geospatial analytics company, Orbital Insight, compared the phones’ 2019 locations with their locations from March through June, and again March through the end of 2020.

Matt Larriva, director of research analytics at FCP, told GrowthSpotter Orlando saw a net growth increase by half a percentage point during the pandemic.

According to their data, Orlando saw 237,549 people relocate to the region and 223,797 people leave, resulting in positive net migration of 13,752 people. Of the people that came to Orlando, most clocked in from Miami, New York and Tampa.

“That’s a little bit less than they usually do, but the fact that Orlando still saw growth is interesting because it’s so tourism driven and tourism was largely shut down,” Larriva said.

Tampa and Jacksonville doubled their in-migrations and picked up a lot of people from Miami and New York, he adds, while Miami lost people at a higher clip than it usually does.

“Real estate is basically the story of population movement,” Larriva said. “You want to find the markets that are going to be the long stable recipients of domestic net migration and good jobs, and that’s where you want to build and be.”

Homebuilders scramble to keep up with record demand

When the economy shut down in March 2020, Central Florida homebuilders began preparing for another prolonged recession mirroring the great recession of a decade before. Instead, they got a boomerang market that surged beyond anyone’s wildest estimate.

“March and April were incredibly scary – just the uncertainty,” Avex Homes President Eric Marks said. “We saw our sales drop 75% in the second quarter.”

Chassity Vega, executive director of the Greater Orlando Builders Association, said the early days of the pandemic felt like PTSD for much of the industry, especially before state and local leaders deemed homebuilders an essential industry. Much of the selling process went virtual, including home tours via FaceTime, drive-thru closings and online design studios.

“During that two-three week time period, we really had to pivot the whole industry toward how to build and sell homes in a pandemic. In my opinion, we did it well,” Vega said.

The combination of low interest rates, work-from-home transition economy and migration patterns drove demand for existing and new homes in and around Orlando while builders worked at a frenzied-like pace to add new supply.

“Look to the middle of the pandemic, where Florida is somewhat open, in a sense, compared to places like California and New York – and even South Florida – and all of a sudden the demand to live in Central Florida has significantly increased,” Vega said.

D.R. Horton, the nation’s largest builder, reported a net increase of 31% for sales orders in the third quarter of 2020. By the fourth quarter, that figure had risen to 81% above the net sales for the same time in 2019. Homebuilding revenues and closings increased 15% year over year.

Taylor Morrison Homes saw its annual revenue in 2020 grow by 29% year over year, to a record $6.1 billion. CEO Sherly Palmer said one of her biggest challenges has been balancing production capacity to keep up with the pace of sales.

“And the demand across all markets, across all consumer groups, is very, very strong,” she said in a recent Yahoo! Interview. “We are seeing it with that first-time buyer, and we can talk about all the different reasons that’s happening coming out of COVID. We’re seeing the 55 active-adult lifestyle buyers coming back.”

Lennar Homes showed its confidence in the market by executing large land deals for suburban projects in Lake and Polk counties and in St. Cloud and Daytona Beach, Division President Brock Nicholas said.

“We did have some locations that were more impacted than others,” Nicholas said.

The company’s annual report noted that housing products and communities that rely largely on international buyers were negatively impacted due to COVID-19. Locally, Lennar hasn’t broken ground on its newest vacation resort community on International Drive, but Nicholas said that delay was anticipated because of environmental issues on the site. “The timing of that community was also more closely tied to the Epic Universe construction schedule than anything else,” he added.

Vega said many local builders shifted their business model to add more speculative homes “because buyers wanted quick sales” and because that way they can factor in the higher lumber and materials cost into the final sale price.

Marks said Avex has a hybrid approach. “We’re working on a model that brings the spec house to the point just before the cabinets and tile go in, so the buyer still gets to make those selections,” he said. “I think most builders are surprised at the sustained increase in sales, but I also think we’re realizing the true attractiveness of Central Florida to people trying to relocate from all over the country.”

Taylor Morrison just expanded its lot inventory in hot markets, like Horizon West and St. Cloud, and the builder is prepping to start construction on Solivita Grand, a huge master-planned community in Poinciana.

“When I look at the demographic tailwinds, I expect demand to keep going,” Palmer said. “We’ve been underbuilding for so many years in this country that even at the pace we’re building to today, it will take us years to catch up for the underbuilding we’ve been doing.”

The pandemic supercharged big growth and big busts in the retail industry

Restaurant and retail businesses embodied both David and Goliath characteristics during the pandemic.

Between an array of store closures from Stein Mart, JCPenney, Pier 1 Imports and Guitar Center, e-commerce platforms like Instacart and Shopify and partnering grocery stores saw exponential growth and success.

Chains like Staples, Dick’s Sporting Goods, CVS and Petco began utilizing the app-based grocery ordering services, and large online brands, such as Chewy, wooed customers away from specialty retailers that didn’t have a strong digital presence.

According to the research firm eMarketer, worldwide retail e-commerce sales grew 27.6% for the year, for a total of $4.28 trillion.

Meanwhile, AMC Entertainment went from generating almost $500 million in revenue a month, to virtually $0 when the shutdown orders were put in place. Year-end sales at Macy’s dropped 29% to $17.3 billion in 2020, according to the New York Times, reflecting a net loss of $3.9 billion for the year ending on Jan. 30.

Local industry experts told GrowthSpotter they believe the pandemic accelerated the prevalence of outdoor seating, online shopping, curbside pick-up and other forms of delivery and carryout options for retail and restaurant businesses.

“All of those things we knew were coming or we expected to see phased in over time… It was much closer to the switch being flipped,” Justin Greider, senior vice president and Florida retail lead at JLL. “[The pandemic] excelled all of the trends we were talking about 18 months ago.”

In the restaurant business, large chains and retail developers are betting last year’s reliance on takeout meals will stick around after the pandemic.

Fast-casual spins on Applebee’s and Outback are expanding throughout the Sunbelt. Earlier this year, Wawa opened its first pick-up window in Philadelphia, and Chipotle is in the midst of rolling out more restaurants with drive-thrus. So far, throughout Central Florida, “Chipotlane” concepts will be in Kissimmee, Winter Springs, Casselberry and by the University of Central Florida. In January, Shake Shack announced it would open its first restaurant with drive-thru lanes at Vineland Pointe.

“Now your most valuable retail centers need to have some drive-thru components,” Gregg Hill, president of Oviedo-based Hill Gray Seven, said. “The drive-thru is critical, and I would say it’s going to get harder to lease up inline space.”

Even dine-in restaurants are establishing pick-up-and-go areas, he adds.

Both Greider and Hill agree, new retail development will be of a smaller scale than before, and will primarily take place close to where people are living in neighboring communities, instead of large regional destinations.

“There was very little new development over the past 12 to 18 months,” Greider said. “We weren’t in a part of the cycle that was seeing large amounts of new retail anyways, so as we’re coming out of [the pandemic] we are seeing demand for some of that new development in areas where retail sales are strong right now.”

Unicorp Development’s Celebration Pointe project was delayed when Dave & Buster’s pulled out and the project had to be redesigned for a new grocery anchor. Maitland-based Equinox Development Properties recently downsized the retail square footage of its planned WaterStar Orlando town center in the Four Corners area of Orange County, giving up nearly 100,000 square feet of retail to build a second apartment complex.

“The era of the million-square-foot shopping center is over,” Hill said. He also believes big anchors are a thing of the past. “That’s why I developed Stonehill Plaza in Oviedo,” he said. “It has 13 different tenants and no anchor… it proves it works.”

Central Florida’s industrial market outshines Orlando’s tourism industry

At the start of his career, CBRE’s David Murphy said it was impossible to separate the symbiotic relationship between tourism in Orlando and its economy.

Much of his business revolved around firms looking to occupy warehouse space in Central Florida that may service the theme parks and attractions in the tourism corridor.

“The initial thought I had during the pandemic was: If they close down the attractions and close down the convention center, the industrial sector is going to collapse,” he said.

But that didn’t happen.

Experts told GrowthSpotter, Metro Orlando’s steady population growth, along with a sharp increase in online shopping and push for shorter delivery times, helped propel more e-commerce tenants to enter and expand in the market.

“We saw an immediate impact in the amount of tenants looking for space within a month of the start of the pandemic,” Murphy said. “We were receiving more calls from users that were trying to adjust their supply chain to fit the demand they were seeing.”

Murphy estimates every billion-dollar increase of e-commerce, creates a demand for an additional 1.25 million square feet of industrial product.

According to a report by Digital Commerce 360, consumers closed out the year spending a little more than $861 billion online with U.S. merchants, up 44% year over year. The increase marks the highest jump in annual U.S. e-commerce retail sales in the last two decades. Last year, U.S. e-commerce growth went up 15.1%.

“Imagine the amount of extra industrial demand we saw in a growing area like Central Florida,” he said. Even with 3.4 million square feet of facilities in the construction pipeline, he believes demand for industrial space is outpacing growth.

When that happens, industrial development sites become competitive and sale prices for industrial buildings shoot through the roof, Larry Kahn, senior director of industrial at Franklin Street’s Orlando office, said. Lease rates and land prices naturally increase too, he adds.

“Finding large sites is extremely difficult, which is why suddenly Apopka became attractive,” he said.

Industrial reports show the most active areas throughout Metro Orlando, in terms of new industrial development, are located in the Silver Star/Apopka and Airport/Lake Nona submarkets.

Distribution hubs and warehouse facilities for companies like Amazon, Goya Foods, Universal Studios Orlando and the Coca-Cola Company have recently set up shop in Apopka.

Amazon is also taking occupancy of 561,750 square feet at Air Commerce Park in southeast Orange County, along with Sprouts Natural Market, which is building out a 134,500-square-foot distribution center at the industrial park.

“There’s several large national developers that want to enter the Orlando market, it’s getting people to accept the right offers,” Kahn said. “Finding the right circumstance to get that deal is going to take work.”

Source: